In a previous blog, I explored why “Minna no Nihongo,” a longstanding staple in Japanese language education, feels outdated. Today, I’ll delve into why this textbook remains so prevalent. Simply put, it’s due to familiarity: teachers are used to it, and Japanese language teaching certifications increasingly advocate methods based on this textbook.

Early Publication of “Minna no Nihongo”

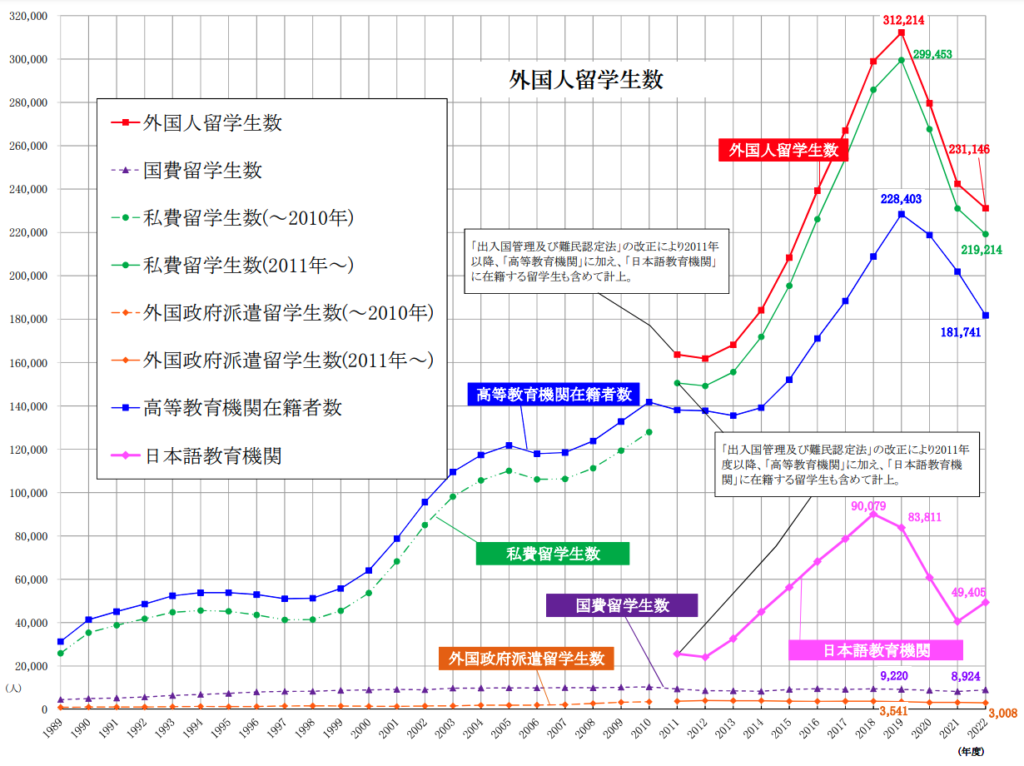

The graph below displays the trends in foreign student enrollment.

- Blue: Foreign students enrolled in higher education institutions

- Green: Privately-financed foreign students

- Red: Foreign students (since 2011, includes students in higher education and Japanese language education institutions)

Triggered by Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone’s 1983 initiative for “100,000 Foreign Students Plan,” there was a surge in both students and language schools, necessitating more teachers and accessible textbooks. First published in 1998, “Minna no Nihongo” predates many alternative textbooks. In an era sparse with choices, “Minna no Nihongo” from 1998, continuing from “Shin Nihongo no Kiso (1990)” and “Nihongo no Kiso (1973),” facilitated teaching for veteran instructors and simplified training for new teachers.

Reluctance to Adopt New Textbooks

Although numerous publishers have since introduced textbooks featuring modern pedagogical approaches, few have seen widespread adoption. For example, “Daichi (2008),” also by the publisher of “Minna no Nihongo,” although clearer and based on the same framework, has remained obscure. The absence of grammar explanations in “Minna no Nihongo” has paradoxically led teachers to develop their own supplementary materials, reducing the need for alternative texts.

Textbook Selection Dominated by Senior Teachers

As the number of foreign students and schools rose, further propelled by Prime Minister Yasuo Fukuda’s 2008 “300,000 Foreign Students Plan,” Japanese language schools multiplied rapidly. Textbook decisions in these schools are typically made by seasoned educators who find “Minna no Nihongo” most user-friendly, hence its continued use. These teachers are reluctant to discard the resources and methods they have developed, and selections often disregard advancements in second language acquisition theory or contemporary teaching strategies.

“Minna no Nihongo” in Teacher Training

With an adoption rate of 72.8% (“2020 Survey of All Japanese Language Schools”), followed by “Dekiru Nihongo” at 10.5%, “Minna no Nihongo” is frequently used in Japanese language schools. This situation has led Japanese Language Teacher Training Courses to adopt “Minna no Nihongo” for class practice. This perpetuates a cycle: “Minna no Nihongo” is used in training courses, making it the default choice in schools, which in turn influences training programs to maintain its use.

Despite innovations by second language acquisition researchers and new textbooks from publishers that incorporate cutting-edge teaching methods, old habits persist. The Japan Foundation’s distribution of “Irodori” for free, which uses a task-based approach, seems to be a reaction to the stagnation in the field of Japanese language education.

How to Teach with “Minna no Nihongo”

Using “Minna no Nihongo” for instruction entirely in Japanese, without grammar explanations or translations, demands specialized skills. Japanese Language Teacher Training Courses focus on imparting these niche skills. In my next post, I’ll explore how they teach using “Minna no Nihongo.”