In my previous article, I discussed the definition of the term “historian” and the problematic “preconceptions” Metatron harbored.

This time, I would like to write about “the meaning of words,” “prejudices,” and “the unreliability of Japanese historical academia,” focusing on posts by Professor Mihoko Oka, an associate professor at the Historiographical Institute, the University of Tokyo. Her approach to historical materials highlights the flaws in Japanese historical academia.

Ubisoft’s revelations about Thomas Lockley’s historical fabrications have also exposed the low credibility of Japanese historical academia.

- The Decline in Credibility of Japanese Historical Academia: Questioning Professor Mihoko Oka’s Reliability

- Unbelievable Statement by Professor Mihoko Oka: Trusting Feelings Over Records

- Is She Emotionally Distorting Historical Facts in Academia? 1: The Usage of the Word “Cafre”

- Her Statements Insult the Japanese Translator from the Showa Era

- Is She Emotionally Distorting Historical Facts in Academia? 2: The Interpretation of “algumas manhas boas”

- She Uses the N-Word Based on Her “Prejudice”: Does She Not Research the Meaning of Words?

- 揮淚斬馬謖, Executing Ma Su with Tears

The Decline in Credibility of Japanese Historical Academia: Questioning Professor Mihoko Oka’s Reliability

From my previous articles, it’s clear that I initially had no ill feelings toward Professor Oka and even expected her to impart accurate knowledge. While her statements reflect extreme liberal ideas, this is common in academia and I didn’t particularly care about it.

However, it appears her ideology might be distorting academic facts. My assumption that an associate professor at the University of Tokyo would be a reliable researcher was an illusion and a prejudice. I will highlight the doubts surrounding her statements here.

She brings too much emotion into academia, potentially disrupting its self-correcting mechanisms and leading to an unhealthy state.

Thomas Lockley’s tendency to spread falsehoods might be rooted in Japanese historical academia’s tendency for believing and propagating what they wish to be true.

Unbelievable Statement by Professor Mihoko Oka: Trusting Feelings Over Records

Professor Oka suddenly sent a reply to Mr. Ram Myers:

私がこの世界に来た時、最初に目に入ったのがラム・マイヤーズさんで、大量のデマが飛び交う中で情報をきちんと整理しようとされている姿がとても好印象でした。ご助力感謝します。ロックリーさんによれば、Wikipedia英文の弥介は、一度改稿したことがあるだけとのこと。私はこれを信じたいと思います

Translation:

Cited from: https://x.com/mei_gang30266/status/1815957081536741463

When I came into this world, the first person I saw was you, Mr. Ram Myers, diligently organizing information amidst a flood of falsehoods, and I was very impressed. I appreciate your help. According to Prof. Lockley, he revised the English Wikipedia page of Yasuke only once. I want to believe this

I was surprised for two reasons:

- Lockley is still lying about editing Wikipedia only once.

- She believes Lockley’s statement despite the available Wikipedia edit history.

1. Lockley is Still Lying About Editing Wikipedia Only Once

Wikipediaの編集記録からすると32回編集されてますが……

Translation:

The Wikipedia edit record shows 32 edits……

It’s amusing that it’s counted. I also summarized in an article, with URLs and images, the edits Thomas Lockley made. Why does he continue to lie?

2. She Believes Lockley’s Statement Despite the Wikipedia Edit History Being Available

Mr. Ram Myers is one of those who meticulously investigated and summarized Lockley’s Wikipedia edits. Professor Oka must have seen his summary as well. Even so, she trusts her feelings over the records. Is she really a historiographer?

Mr. Ram Myers did not respond to this Professor Oka’s reply. I understand his silence. People like him, who verify primary sources, would despise liars.

Lockley seems to lie freely to those ignorant of the field (in this case, the elderly Professor Oka). His action betray her trust and is despicable.

Anyway, this clearly shows that Professor Oka makes decisions based on her feelings without examining primary sources (in this case, Wikipedia’s edit history). How is this stance acceptable for a scholar? Reflecting on it, she tends to interpret historical materials arbitrarily.

Is She Emotionally Distorting Historical Facts in Academia? 1: The Usage of the Word “Cafre”

Her post contains many illogical parts for a researcher. In response to the question, “Where is ‘samurai’ written in the Japanese translation of the Jesuit Japan Annual Report?”, she replied:

原文には「Cafreカフル人」とはっきり書かれており、「奴隷」を想起させる単語は一切入っておりません。「黒奴」としたのは、昭和時代の日本人翻訳者の偏見です。私の過去のポスティングをご覧いただければ。

Translation:

Cited from: https://x.com/mei_gang30266/status/1815030671720747281

The original clearly says “Cafre,” and there is no word that evokes “slave.” The translation “black slave” is a prejudice of the Japanese translator from the Showa era. Please read my past posts.

This response doesn’t address the question of “where ‘samurai’ is written.” Setting aside the fact that conversation is not happening, the word “Cafre” itself evokes “slave,” making her statement that “there is no word that evokes ‘slave'” incorrect. She shouldn’t have made such an emotionally definitive assertion as a scholar.

I immediately felt her statement was strange. When I created my English translation, I referred to the original Portuguese text for “Cafre,” as “black slave” is a sensitive term. After thorough research, I decided “black slave” was an appropriate translation.

I read Portuguese Wikipedia while consulting a Portuguese-English dictionary. Considering how Cafre was treated, I ultimately chose “black slave.” Her statement dismisses my efforts and those of a Japanese translator from the Showa era as “prejudice,” which is insulting.

To avoid being called a racist unfairly, here are the reasons why the Japanese translator from the Showa era and I translated Cafre as “black slave.” If you’re not interested, please skip to the next section.

Portuguese Wikipedia Explanation 1

The Portuguese Wikipedia page “Cafre” states the following:

Seguindo a terminologia de Leão, o Africano, o clérigo e historiador inglês Richard Hakluyt (1552 – 1616) igualmente se refere a essa população como Cafars ou Cafari, no sentido de infiéis ou descrentes. Ao falar dos escravos (“slaves called ‘Cafari’ “) e de certos habitantes da Etiópia (“and they use to go in small shippes, and trade with the Cafars”) Hakluyt usa aqueles dois termos

Translation (using machine translation):

Cited from: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cafre

Following the terminology of Leo Africanus, the English clergyman and historian Richard Hakluyt (1552-1616) likewise refers to this population as Cafars or Cafari, in the sense of infidels or unbelievers. When speaking of slaves (“slaves called ‘Cafari'”) and certain inhabitants of Ethiopia (“and they use to go in small ships, and trade with the Cafars”), Hakluyt uses those two terms

Portuguese Wikipedia Explanation 2

The Portuguese Wikipedia page “Cafre (povo)” states the following:

Significa “qualquer indivíduo cujo fenótipo remonta mais ou menos às origens africanas e escravo malgaxe, conforme descrito pelo sociólogo Paul Mayoka em seu ensaio “A imagem do cafre”.

Translation (using machine translation):

Cited from: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cafres_(povo)

It means “any individual whose phenotype more or less traces back to African origins and Malagasy slave, as described by the sociologist Paul Mayoka in his essay ‘The Image of the Cafre’.”

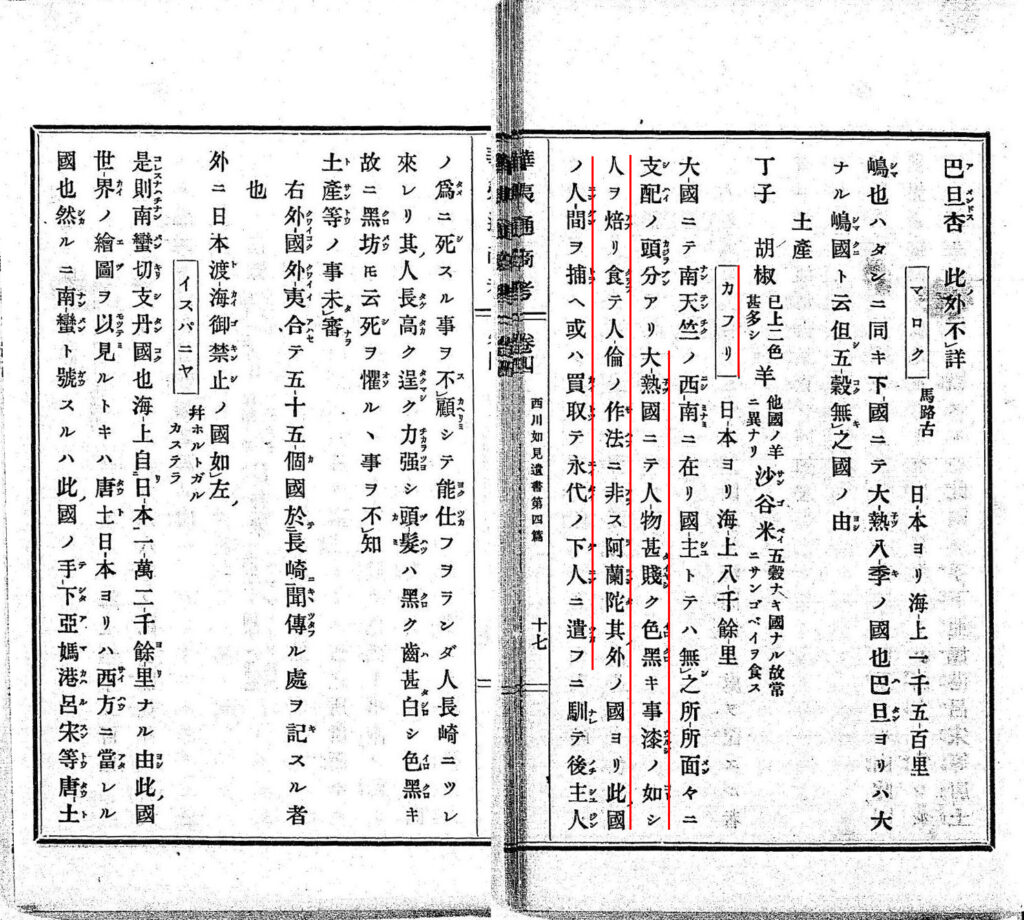

Explanation from 華夷通商考 (Kaitsūshōkō)

In 華夷通商考 (Kaitsūshōkō, 1695), a geographical book 100 years after Yasuke’s time, there is a description of “カフリ (Cafre)”. Although not a 16th-century Portuguese description, as the Dutch had taken global hegemony by the 17th century, it would be still useful.

弥助から100年後の地理書『華夷通商考』の記述

「大熱国にて人物甚だ賤しく、色黒き事漆の如し。人をあぶり食らうて人倫の作法に非ず。オランダその他の国よりこの国の人間を捕えあるいは買い取って永代の下人に遣う。」

読み取れること

1.カフルは奴隷貿易の対象

2.日本人はカフルを蔑視しているTranslation:

100 years after Yasuke, the geographical book ‘Kaitsūshōkō’ describes:“The people in the country of great heat are extremely ignoble, their skin as black as lacquer. They roast and eat people, which is not in line with human norms. The Dutch and other countries capture or buy people from this country and use them as lifelong servants.”

From this, we understand the following:

Cited from: https://x.com/laymans8/status/1809931585942167688

1. Cafre was a target of the slave trade

2. The Japanese looked down on Cafre

Circumstantial Evidence 1: If He Wasn’t a Slave, Why Didn’t the Missionaries Name Him?

Nobunaga gave him the name “Yasuke.” If the Jesuits didn’t consider him a slave, why didn’t they call him by name?

Circumstantial Evidence 2: If He Wasn’t a Slave, Why Could He Be Given as a Gift?

Why were the Jesuits able to give him to Nobunaga like an object? Wasn’t he treated as an object rather than a person?

From the above, it is almost certain that Yasuke was a slave of the Jesuits.

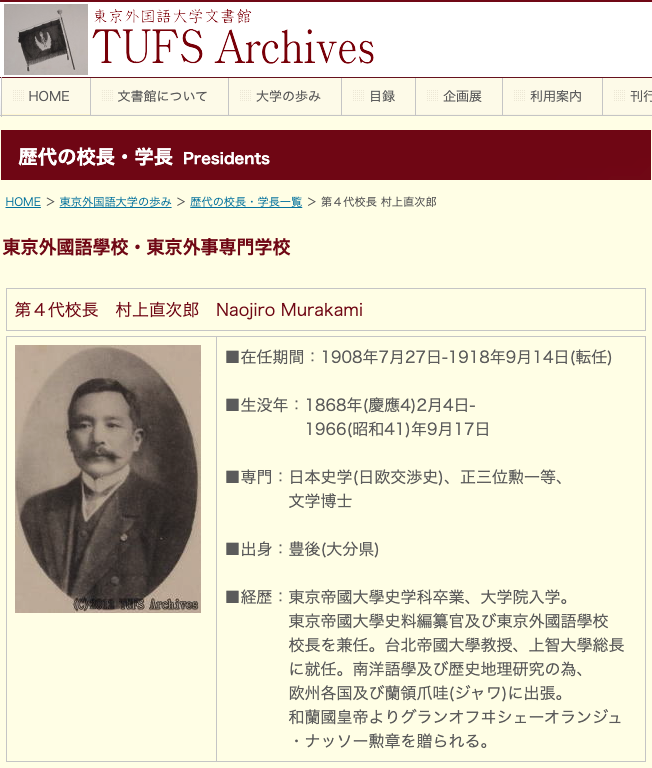

Her Statements Insult the Japanese Translator from the Showa Era

The person who translated the Jesuit Japan Annual Report was Professor 村上直次郎 (Naojiro Murakami). He was a historian who served as the president of Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, from which I graduated, and translated numerous Jesuit records.

Incidentally, Professor Oka graduated from Osaka University of Foreign Studies. Tokyo University of Foreign Studies is now the only national university in Japan specializing in foreign studies and languages since Osaka University absorbed Osaka University of Foreign Studies.

Professor Murakami must have devised an appropriate translation with great effort. Considering their origin and treatment, he came up with the simple and easy-to-understand term “黒奴 (kokudo, black slave).” I think this is a brilliant translation.

In contrast, Professor Oka’s transliteration of “カフル人 (Cafre people)” doesn’t make it clear what the word means. It’s ridiculous for a modern scholar to make the term “Cafre” in historical materials politically correct based on her own ideology without considering how the term was actually used.

At least Professor Murakami’s translation is not wrong. However, Professor Oka’s claim that there is no word that evokes “slave” is clearly wrong.

Is She Emotionally Distorting Historical Facts in Academia? 2: The Interpretation of “algumas manhas boas”

Today, she again showed that she arbitrarily interprets historical materials.

https://www.sankei.com/article/20240805-2RDCMCMKMNFYFOGXMRGPCIT2NI/

原文をみた。これまでの訳本の間違いを発見。1581年10月8日付のロレンソ・メシアの書簡の弥助に言及した箇所「tinha muitas forcas & algumas manhas boas」は「非常に力があり、いくらかの芸が出来る(既存訳)」ではなく、「非常に力があり、資質に優れている」と訳すべき。Translation:

Cited from: https://x.com/mei_gang30266/status/1820863453609042172

https://www.sankei.com/article/20240805-2RDCMCMKMNFYFOGXMRGPCIT2NI/

I read the original text. I found a mistake in the previous translation. The passage mentioning Yasuke in Lorenzo Mesia’s letter dated October 8, 1581, “tinha muitas forcas & algumas manhas boas,” should be translated not as “very strong and capable of some tricks (existing translation),” but as “very strong and of good quality.”

She again makes an emotionally definitive assertion, but the existing translation is not wrong.

- algumas: some

- manhas: cunning, skills, tricks

- boas: good

While her more abstract interpretation is possible, the existing translation is clearer and more understandable. Considering the previous description of “if put the black slave on show for profit, it would be easy to earn eight thousand to ten thousand cruzados in a short time,” it is clear the Jesuits would have treated Yasuke like a spectacle.

Moreover, the part she mentioned explains why Nobunaga liked Yasuke. Nobunaga could immediately see Yasuke was “strong,” but he wouldn’t have immediately known he was “of good quality.” It is more natural to assume Yasuke performed some kind of trick that pleased Nobunaga.

However, looking at her conversation on X, it seems that Professor Oka wants to portray Yasuke as having noble martial arts skills.

ちょっと質問ですが、引用している辞書を読む限り、「資質に優れている」ではなく「貴族の相応しい芸術(arte)と行動(exercicios)」なので「礼儀・行儀・作法がいい」なのでは?

Translation:

Cited from: https://x.com/ParallelPain/status/1821392419772121329

Just a quick question, but according to the dictionary you’re quoting, wouldn’t “good courtesy, manners and etiquette” be a correct translation, not “of good quality” since it says “arts (arte) and behaviors (exercicios) befitting a noble”?

そういう理解もできると思います。私が「貴族云々」の部分まで紹介してしまうと、必ずやおかしな議論が沸き起こって、収拾がつかなくなるので。いずれにしても、かなりポジティブな意味しかありません。exerciciosはどちらかというと武芸の鍛錬の意味がありますが、これも明言は避けたいところです。

Translation:

Cited from: https://x.com/mei_gang30266/status/1821397435723509860

I think that’s a valid interpretation too. If I were to bring up the part about “nobility yada yada,” it would undoubtedly spark some strange debates that would be hard to manage. In any case, the meaning is quite positive. “exercicios” leans more towards martial arts training, but I’d rather avoid stating that explicitly.

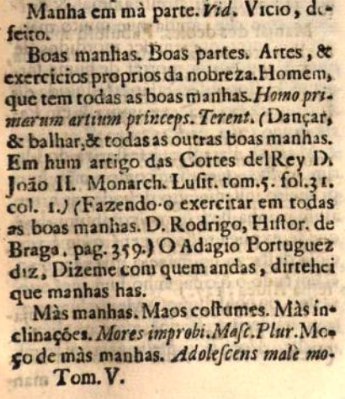

However, the dictionary she is quoting also includes “Dançar & bailar” (dance and leaping). I found a clearer image of that page:

Boas manhas. Boas partes. Artes, & exercicios proprios da nobreza. Homem, que tem todas as boas manhas. Homo primarum artium princeps. Terent. (Dançar, & bailar, & todas as outras boas manhas. Em hum artigo das Cortes delRey D. João II. Monarch. Lusit. tom. 5. fol. 31. col. 1.) (Fazendo-o exercitar em todas as boas manhas. D. Rodrigo, Hiftor. de Braga, pag. 359.) O Adagio Portuguez diz: Diz-me com quem andas, dir-te-hei que manhas has.

Translation (using machine translation):

Cited from: Vocabulario Portuguez e latino (Volume 05: Letras K-N), Bluteau Rafael, 1716

Boas manhas. Good habits. Good qualities. Arts and exercises appropriate for nobility. A man who possesses all good habits. “Homo primarum artium princeps.” Terence (Dancing, & leaping, & all other good habits). In an article from the Courts of King D. João II. Monarch. Lusit. Vol. 5, Fol. 31, Col. 1 (Making him practice all good habits. D. Rodrigo, Historian of Braga, p. 359). The Portuguese saying goes: “Tell me who you walk with, and I’ll tell you what habits you have.”

Even as a layperson, knowing the record of Hideyoshi watching a dance performance by black slaves, I could speculate that “boas manhas” might have referred to Yasuke’s dancing.

Record of Hideyoshi Making Black Slaves Dance in 1593

Just 11 years after Nobunaga’s death, in 1593, there is a record of Hideyoshi naturally making black slaves dance and everyone laughing out loud. I found a paper which translated it into English:

Playing Changes: Music as Mediator between Japanese and Black Americans (PDF)

When the Captain General Gaspar Pinto da Rocha came to visit Taikō-sama [Hideyoshi] in Nagoya, he brought with him a guard of kaffirs with golden spears and kaffirs dressed in red with a drum and fife. Taikō-sama made the kaffirs dance to the sound of the drum and fife. And as they are naturally very inclined to dance, it was something that made those who saw them burst into laughter, because, without any order or prior plan, they jumped from here to there and, as they began, no matter how much he told them it was enough, nothing could make them stop dancing. Taikō-sama ordered that each be given a white catabira, which are shirts of very fine linen and open inside. And when I told them to put them on their heads for the esteem and honor of those who gave them, they tied them on their heads like a lascar’s cap. It was a show that entertained Taikō-sama and all the court that was there.

Cited from: Playing Changes: Music as Mediator between Japanese and Black Americans (PDF)

As an expert in Jesuit Portuguese literature, Professor Oka should have been aware of this record. Midori Fujita’s book, “アフリカ「発見」―日本におけるアフリカ像の変遷 (The ‘Discovery’ of Africa—The Changing Image of Africa in Japan) (2005),” also references this.

So why did she avoid mentioning the possibility of “Dançar & bailar” (dance and leaping) and instead choose the ambiguous and unclear translation “of good quality”?

From her statements, I sense a desire to rewrite the fact that Yasuke was a slave and treated like a spectacle by the Jesuits. This stance of Japanese historians towards historical materials might have led to Lockley’s eccentric theories.

This paper also includes other interesting passages:

Interesting Passage 1: Contrary to Professor Oka’s Ideology, It Clearly Identifies Them as “Slaves.”

Although Japanese may have encountered African traders in China during the Tang and Song dynasties, the first contacts confirmed in the historical record occurred in 1546, three years after Portuguese traders first arrived in Tanegashima, bearing the arquebus that would facilitate the eventual political reunification of the archipelago. Enslaved people from southeast Africa accompanied Captain Jorge Álvares, who noted that Japanese “took great pleasure in seeing the black races.”Japanese called them kafu or kafayajin, transliterations from the Portuguese cafre, a term for non-Muslim East Africans derived in turn from the Arabic kāfir, “infidel.”

Cited from: Playing Changes: Music as Mediator between Japanese and Black Americans (PDF)

Looking at historical facts objectively, it’s clear they were slaves.

Interesting Passage 2: “African Samurai, Yasuke” Myth Is Mentioned

The “African Samurai, Yasuke” myth created by Lockley has become so well-known that it’s mentioned in such an academic papers as if it were common knowledge.

In addition to the famous “African Samurai” Yasuke, perhaps hundreds of Africans (overwhelmingly if not completely males) who came with the Portuguese and Spaniards remained in Japan for the rest of their lives.

Cited from: Playing Changes: Music as Mediator between Japanese and Black Americans (PDF)

Interesting Passage 3: The Dutch Treated Black Slaves with Extreme Brutality.

Dutch Studies scholar (rangakusha) Hirokawa Kai denounced the “red-haired barbarians” (kōmō no banjin) for treating enslaved Africans with such brutality; he reported that when one became seriously ill, the Dutch would poison him to death.

Cited from: Playing Changes: Music as Mediator between Japanese and Black Americans (PDF)

Horrible…

It’s important to note that this description is from the 18th century and pertains to the Dutch, not to the Jesuit Portuguese records, but clearly, they were treated as slaves.

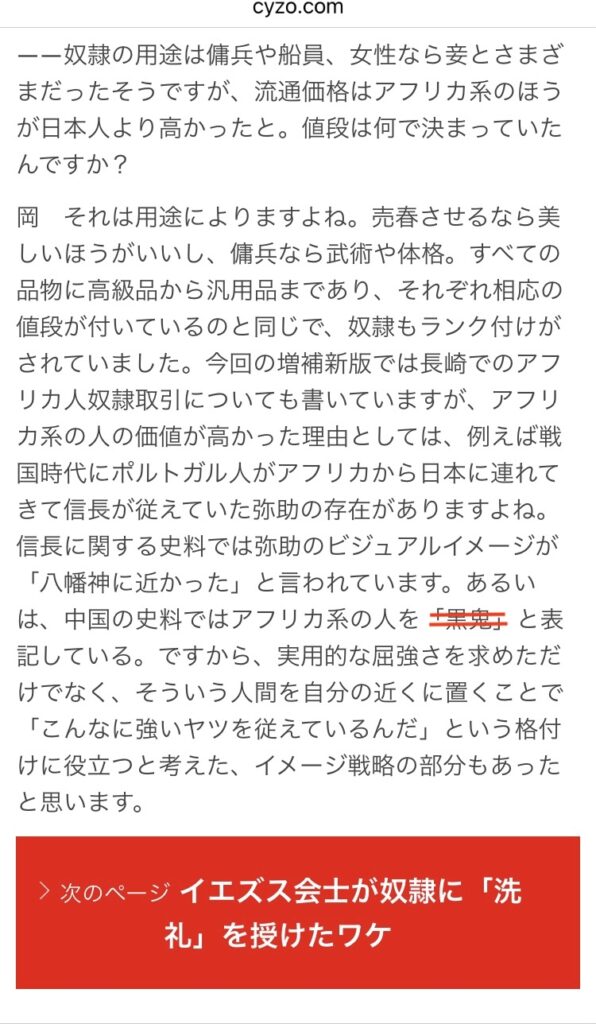

She Uses the N-Word Based on Her “Prejudice”: Does She Not Research the Meaning of Words?

Even though she criticizes the translation of Cafre as “black slave” ignoring historical facts, she astonishingly used the Chinese N-word in an interview. This clearly shows she does not research how words are actually used. The original article has been deleted, so I’m attaching my screenshot.

――奴隷の用途は傭兵や船員、女性なら妾とさまざまだったそうですが、流通価格はアフリカ系のほうが日本人より高かったと。値段は何で決まっていたんですか?

岡 それは用途によりますよね。売春させるなら美しいほうがいいし、傭兵なら武術や体格。すべての品物に高級品から汎用品まであり、それぞれ相応の値段が付いているのと同じで、奴隷もランク付けがされていました。今回の増補新版では長崎でのアフリカ人奴隷取引についても書いていますが、アフリカ系の人の価値が高かった理由としては、例えば戦国時代にポルトガル人がアフリカから日本に連れてきて信長が従えていた弥助の存在がありますよね。信長に関する史料では弥助のビジュアルイメージが「八幡神に近かった」と言われています。あるいは、中国の史料ではアフリカ系の人を[N-word]と表記している。ですから、実用的な屈強さを求めただけでなく、そういう人間を自分の近くに置くことで「こんなに強いヤツを従えているんだ」という格付けに役立つと考えた、イメージ戦略の部分もあったと思います。

Translation:

――Slaves were used for various purposes, such as mercenaries, sailors, or concubines if they were women. Prices were higher for Africans than Japanese. What determined the price?Oka: It depends on the purpose. Beautiful ones were better for prostitution, and those with martial skills or good physique for mercenaries. Just like any goods, from high-end to general, there were corresponding prices for slaves. In the new edition, I also write about African slave transactions in Nagasaki, and the reason for the high value of Africans was, for example, the presence of Yasuke, who was brought from Africa to Japan by the Portuguese and served Nobunaga. Historical sources say Yasuke’s visual image was “close to Hachiman God (八幡神).” Also, in Chinese records, Africans were referred to as “[N-word]”. So, they sought not only practical strength but also would have believed that having such a strong person nearby would serve as an image strategy, conveying the message, “I have such a strong person under my command.”

Cited from: https://cyzo.com/2021/02/post_268095_entry.html

Many Japanese pointed out that Professor Oka herself makes baseless statements about Yasuke’s appearance being “close to Hachiman God,” much like Lockley. However, as someone who understands Chinese, I was most surprised that she quoted the Chinese N-word in her subsequent statement. The following combination of two Chinese characters is the N-word:

- 黒: black

- 鬼: ghost, demon

The character “鬼” has a different meaning in Japanese and Chinese. In Japanese, it means ogre, while in Chinese, it means ghost. The difference is evident in the results of the Google search in Japanese and the Baidu search in Chinese.

She likely interpreted the Chinese N-word as a “strong black ogre” based on the Japanese image of “鬼,” but this is wrong, and using this word is problematic. The Chinese word “鬼” does not have the meaning of “tangibly strong”.

Moreover, in Japan, the character “鬼” does not carry such a strong insult, but in China, it is insulting. This character is also used in the word that insult Japanese people. I don’t want to explain it here, so please look it up yourself if you are interested.

为什么作为中文母语的我没有听过这种说法。

❓Translation:

Why have I, as a native Chinese speaker, never heard this expression?

❓

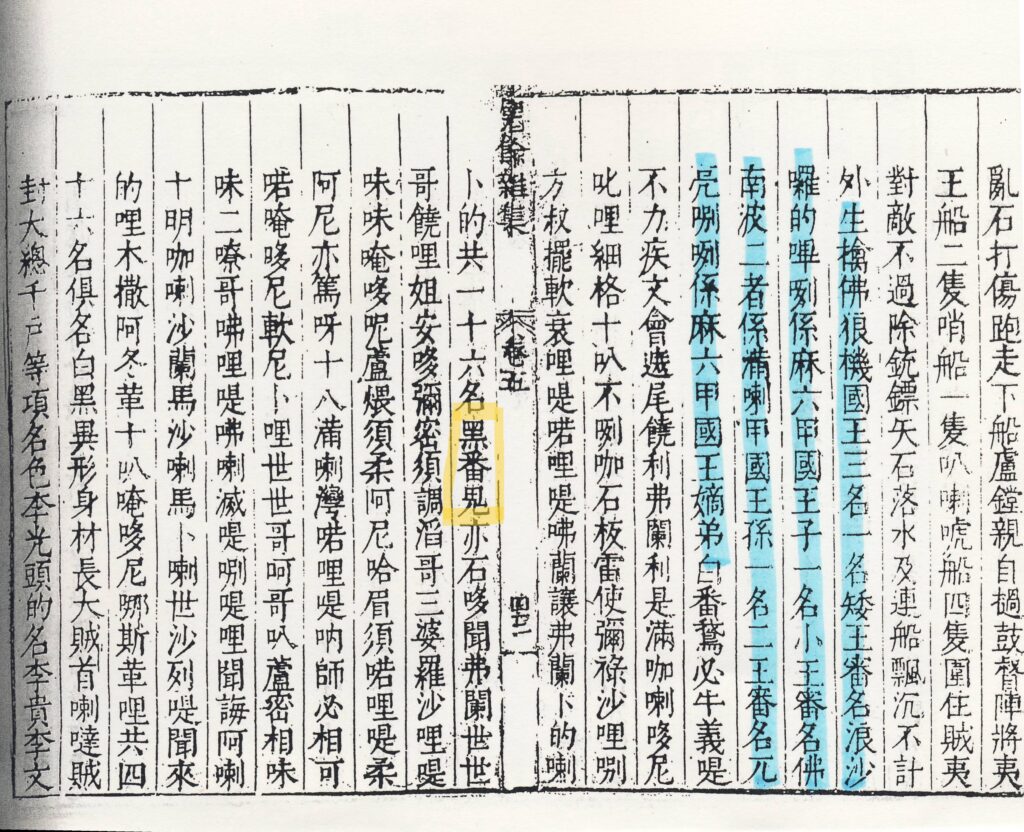

Chinese people themselves say like this. Professor Oka should accept that she was spouting without any basis. She silently posted a “source” on X, but deleted it. I cite the image she posted at that time.

朱紈『甓余雑集』

Translation:

Cited from: https://archive.is/Fe78d

Zhu Wan’s “Piyu Zaji”

I won’t provide the translation since it’s difficult to translate classical Chinese accurately. However, what she highlighted in yellow seems to be a derogatory term for people with black skin from Southeast Asia. What was she trying to say here?

- 黒: black

- 番: barbarian

- 鬼: ghost

This site lists derogatory terms for foreigners in the Ming Dynasty. African blacks are described as follows:

- 極: extremely

- 黑: black

- 番: barbarian

She probably didn’t research the meaning of the words and decided on her own that the term meant “strong black man”, based on Japanese “prejudice”.

She Erases Inconvenient Facts

When asked about the deletion of that interview article, she responded:

「サイゾー」の記事が閲覧できなくなっているようなのですが、やはり自身で執筆されず、編集部が依頼したライターが文字起こしした内容は本意ではなかったという理解でよいでしょうか。

Translation:

Cited from: https://x.com/SatoshiMasutani/status/1821369729149223175

It seems the article on “Cyzo” is no longer accessible. Is it correct to understand that you didn’t write it yourself, and that the content, transcribed by a writer hired by the editorial department, didn’t fully reflect your intentions?

はい。ただ、公開前に自分でも一度は目を通したはずなので、見落とした点に関しては、自身の責任を認めます。

Translation:

Cited from: https://x.com/mei_gang30266/status/1821372431522791658

Yes. However, I should have reviewed it myself before it was published, so I acknowledge my responsibility for any oversights.

In a follow-up post, she added the following, but later deleted it:

因みに、全く思ってもいなかったことが書かれているわけではなく、晩年自身の神格化に努めていた信長は、自分のビジュアルイメージとして、軍神のような姿の弥助を眷属として脇に配したかったのではないか?、といったようなことを言った記憶はあります。

Translation:

By the way, it’s not that the article contains anything I didn’t think at all, but I do remember saying something like, “In his later years, as Nobunaga was striving to deify himself, he might have wanted to position Yasuke, with his god of war-like appearance, as a divine servant by his side as part of his visual image.”

Where is Yasuke, with his god of war-like appearance?

While I appreciate her small gesture of honesty, in the end, she is a scholar who erases inconvenient facts.

It’s absurd that a scholar who arbitrarily interprets records without verification, uses the N-word in an interview, and erases inconvenient facts holds the position of associate professor at the Historiographical Institute of the University of Tokyo.

And it is funny that she, ignorant of secular matters, thought the Chinese N-word was a good term while in her ivory tower.

Again, I can’t help but think the Japanese historical academia’s tendency to present theories and respond to interviews based on their whims and prejudices might have given rise to a perfidious historian like Thomas Lockley.

揮淚斬馬謖, Executing Ma Su with Tears

Professor Oka may not be familiar with Chinese idioms, but there is an old Chinese saying, “executing Ma Su with tears”:

refers to a historical event during the Three Kingdoms period in China, involving Zhuge Liang (諸葛 亮 a famous strategist and statesman) and his subordinate Ma Su (馬謖).

- Ma Su was a trusted advisor of Zhuge Liang, but he made a critical error during a military campaign by not following Zhuge Liang’s orders.

- His mistake led to a significant defeat.

- Zhuge Liang, despite his personal affection and trust in Ma Su, decided to execute him to uphold military discipline and responsibility.

This idiom conveys the idea of making a painful decision for the greater good or the sake of justice, even if it involves punishing someone close or beloved.

Thomas Lockley abused his position as an associate professor at Nihon University and fabricated history through intellectual dishonesty. If such violations of research ethics are overlooked, there is no future for Japanese historical academia.

Even if they are not experts in Chinese history, those in academic authority should take this idiom to heart.