This article discusses historical vocabulary within the context of primary sources. No discriminatory intent is implied. I do not evaluate past terms by modern English standards alone because judgments about language depend on time, place, and language community.

It has been a while since my last post. The previous one was 8 months ago. Lately I have been busy writing a number of Japanese articles about Yasuke, which I plan to translate into English later.

After that previous article, however, a student told me, based on a misunderstanding, that I might be a potential racist.

I ended up losing a new student I had only just met. That is disappointing. Looking back on what happened, the situation was somewhat complicated, and to be honest, I feel it was unfair.

- Background

- On the N-word

- Japanese Readers Wouldn’t Recognize the N-word if Censored

- Misunderstandings About “カフル人 (Kafuru-jin = Kaffir people)”

- The Root of the Misunderstanding: Applying Modern English to a Historical Term

- Presentism: Judging the Past by Today’s Values

- Anglocentrism: Treating English as the Global Standard

- Going Forward, I Will Add Annotations, But…

- I Don’t Want English to Be Treated as the Global Standard

- The N-word in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

- A Restaurant Named Kaffir Lime

- The Japanese “外人” and the Chinese “外人”

- Linguistic and Cultural Isolation in the United States

- I Wish Student X Had First Questioned His Own Assumptions

- It Is Hard to Question One’s Own Preconceptions

- For Those About to Learn a Foreign Language: Don’t Assume English Meanings Are Absolute

- In Conclusion: Though I Lost Something, I Also Learned Something

Background

Here is a brief outline of what happened:

- Student X thought that the word “カフル人 (Kaffir people)” in eich-y’s post, which I had quoted in my earlier article, was discriminatory.

- He was also offended by the appearance of the uncensored N-word in the article.

- He concluded that by quoting the post, I (Naoto) seemed to be in agreement with eich-y’s racism, and decided to stop taking lessons with me.

- In reality, the person who first used the term “カフル人” was not eich-y, but Mihoko Oka.

- Oka herself explained that “カフル人” comes from the 16th-century Portuguese term Cafre, which at the time was not necessarily derogatory.

- Eich-y simply borrowed Oka’s wording in his reply to her.

- I (Naoto) merely quoted these posts in chronological order and translated them faithfully into English.

- As for the N-word, whenever I quoted it or wrote it in English, I always rendered it as “[N-word].”

- What Student X found problematic was actually my Japanese-language explanatory post for Japanese readers that I had quoted in the article.

- In that context, the word was left uncensored, because Japanese readers would not understand what the word referred to if it had been hidden.

What I want to emphasize in this article is:

- The misunderstanding arose from presentism (applying modern English sensibilities to examples in other languages and eras) and Anglocentrism (treating English norms as universal).

- I do not condone discrimination. In fact, I warned Oka against using discriminatory terms.

- Going forward, I will respect the original meaning of historical terms while adding clearer notes, and I ask readers to approach them with an awareness of historical and linguistic context.

A Fun Trial Lesson

Student X, who lives in a rural part of the United States, is an anime enthusiast. He found me, also a fan of anime, and booked a trial lesson.

During the lesson, we exchanged recommendations and had a lively, enjoyable conversation.

As soon as the trial ended, he booked another session for the following week.

An Unexpected Message

Two days before that second lesson, however, I received a very long message.

Because it was marked “confidential message,” I will only summarize the main points here, to avoid others falling into the same misunderstanding as Student X. To show maximum respect for him, I will refrain from quoting directly:

- Seeing you (Naoto) cite comments from openly prejudiced person who intentionally used offensive derogatory words to support your objective made me suspect you might share similar views.

- Specifically, I felt that eich-y’s use of “K***,” as well as the uncensored N-word that appeared in the article, were disrespectful.

- I decided to find another teacher, because I do not want to call someone my teacher who might see me as less than a person.

His message contained many factual errors, which I will explain shortly. Before that, I want to make one important point clear: I am half Thai and half Japanese. Growing up as a mixed Southeast Asian child in the countryside of Japan, a largely monoethnic country, was extremely difficult. Student X likely did not know that I myself have endured racial discrimination for much of my life.

On the N-word

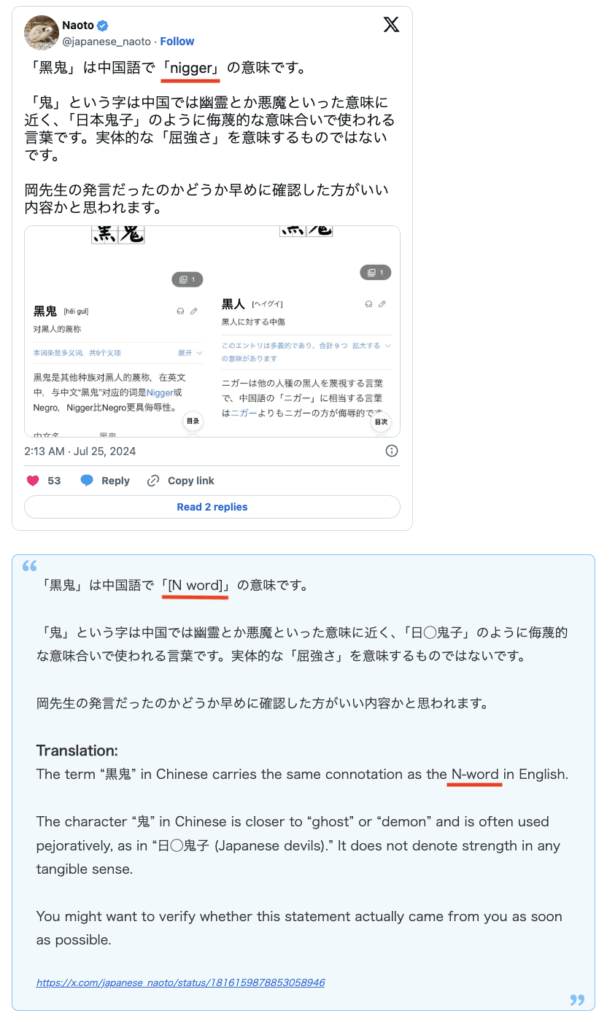

In my article, whenever the N-word appeared in English sentences or in translation, I consistently rendered it as “[N-word].” What Student X referred to was actually a Japanese-language post on X that I had quoted in the article.

Japanese Readers Wouldn’t Recognize the N-word if Censored

In that post, I was explaining a Chinese slur in Japanese, for a Japanese audience, not for English speakers. It is a mistake to assume that Japanese readers will immediately recognize “N****” and understand what it stands for.

Think of another language. If I introduced a Thai slur but wrote it as “H**,” would you know what it meant?

Would you recognize Japanese slurs? Korean ones? Mongolian ones? What about those in every other language in the world?

Of course not. So why should English be treated as universally understood, and why must words be censored in Japanese texts, as if English sensitivities were the global norm?

This way of thinking is what can be called Anglocentrism.

Why I Censored “日◯鬼子 Japanese Devil” (You Can Skip)

Some sharp-eyed readers might point out, “But you censored the word ‘日◯鬼子 (Japanese devil),’ isn’t that contradictory?” To be honest, this is a minor point, and you can skip it if you like. I only did it to prevent negative effects on Google search results.

Compare my X post with the quotation in the article. In my original post about the Chinese N-word, I used the Chinese character 黑. But in the Japanese text quoted in the article, I deliberately changed it to the Japanese character 黒. By altering the script, I ensured that Google’s algorithm recognized the text as Japanese, not as a slur.

However, the four-character slur “日◯鬼子” looks identical in both Japanese and Chinese. If I had quoted it verbatim, Google would have automatically flagged it as a Chinese racial slur. That is why I censored it.

In fact, that original post contained the N-word, and because some of my critics reported it, the post was restricted in visibility. The irony is that the post itself was warning readers: “Be careful, the Chinese word Oka used is essentially the N-word.” Likewise, when I quoted the N-word directly from Russell’s paper into an X article, the post was automatically restricted immediately after publication.

I accept X’s rules since it is a U.S.-based platform. To avoid unnecessary trouble and future restrictions, I have decided that when posting such words, I will censor them even in Japanese contexts, or else render them phonetically in Japanese.

Misunderstandings About “カフル人 (Kafuru-jin = Kaffir people)”

This was the main reason Student X believed I was a racist, and it is also the central theme of this article. His reasoning went like this:

- Eich-y intentionally used the derogative word “Kaffir,” which is “racist.”

- Naoto quoted Eich-y’s “racist” post in his article.

- Therefore, Naoto must hold similar “racist” views.

But in reality, the situation was different:

- It was Mihoko Oka who first used the term “カフル人.”

- She had previously explained that it was not a derogatory expression.

- Eich-y simply borrowed Oka’s wording in his reply to her.

- I (Naoto) merely translated their words faithfully into English.

I included their exchanges in chronological order in my article. Why Student X overlooked the first step is unclear, but as a result, only points three and four were noticed, and I was unfairly labeled a potential racist. That was very unfortunate.

To clarify, here is the full sequence of their posts. In that article, I quoted Oka’s first post and eich-y’s second and third posts:

まぁ、ジョルジ・アルヴァレスの日本報告(1548)には早くも日本人のカフル人に対する接し方が書かれてますし。岸野久『西欧人の日本発見』1989、66頁。同じ報告にやはりカフル人と仏像の関連付けも見え。仏像とカフル人の関連付けはフロイスやコックスも書いているというのは、軽くはない事実ですね

Translation:

https://x.com/mei_gang30266/status/1849238970896650482

Well, Jorge Álvares’s Japanese reports (1548) describe how the Japanese interacted with Kaffir people. Hisano Kishino, “The Discovery of Japan by Westerners,” 1989, p. 66. That report also connects Kaffir people to Buddhist statues. Luís Fróis and Richard Cocks made similar observations, so this is no trivial matter.

岡美穂子先生、それは単に西欧人が日本の仏像を見て「カフル人みたいに黒いのう」と思ったことを岸野氏が記載しただけで、日本人が弥助を仏だと思ったという事は全く意味しませんが…

私、当時の日本人が黒人を仏と思うほどリテラシーが低かったとは思いません

仏像と黒人の黒には大きな違いがありますTranslation:

https://x.com/y_eich26389/status/1849413673179320748

Professor Mihoko Oka, that only means that Westerners looked at Japanese Buddhist statues and thought, “He is black like Kaffir people,” as Mr. Kishino recorded. It does not at all mean that Japanese people considered Yasuke a Buddha…

I don’t think the Japanese of that time were so lacking in comprehension that they believed black people were Buddhas.

There’s a huge difference between the black of Buddhist statues and the black of Black people.

簡単な事です。

黒人は黒い肌ですが普通に色の付いた服を着ています。

一方、仏像は当たり前ですが服まで全部真っ黒ですね?

これは素材的に一体的に作成されているから肌も服も黒一色になっているだけだと理解するリテラシーはあった事でしょう!Translation:

https://x.com/y_eich26389/status/1849416458008400096

It’s simple.

Black people have dark skin but wear normally colored clothing.

On the other hand, Buddha statues, as a matter of course, are entirely black including their clothing.

Japanese people at the time would have had the comprehension to understand that this was simply because the statues were made from a single material, resulting in both the skin and clothing being uniformly black!

更に言うと、古い木造仏は真っ黒になっていても、当時の新造の仏像なら鮮やかに彩色された物も当然に目にしていた筈で、当時の日本人に仏像・仏は真っ黒な色をしているものという固定観念があったとは思えません

https://x.com/y_eich26389/status/1849417647622111629

黒い仏像を見てカフル人を連想するような発想は西欧人の浅はかな連想に過ぎないのでは?

Translation:

Furthermore, even if old wooden Buddha statues had turned completely black over time, newly made statues at the time would have been brightly painted. People would have regularly seen these vividly colored Buddhas, so it’s hard to believe that the Japanese of that era had a fixed idea that Buddha statues or Buddha himself were inherently black.

The idea of looking at a black Buddha statue and associating it with Kaffir people seems to be nothing more than a shallow assumption made by Westerners.

服も含めて真っ黒になった仏像を見てカフル人を連想した西欧人がいたというだけの話で、色の付いた服を着て露出した顔や手足だけが真っ黒い弥助を見て日本人が「仏だ!」と思ったなどと言う主張は全く信じるに当たらないと思います。

https://x.com/y_eich26389/status/1849418777215004894

Translation:

So in short, it was only that one Westerner looked at entirely black statues, including clothes, and associated with Kaffir people. But it is utterly unbelievable that the Japanese saw Yasuke, whose clothing was colored, with only his exposed face and limbs black, and they thought, “He is a Buddha!”

It is clear from this that eich-y was simply responding to Oka using her terminology. His replies were constructive and not racist at all. The source of Student X’s anger was obviously the word カフル人, but if that was the issue, the criticism should have been directed first at Oka, not at Eich-y, and certainly not at me.

The Root of the Misunderstanding: Applying Modern English to a Historical Term

Leaving aside Student X’s factual mistakes, was the word カフル人 actually derogatory?

Oka Said “カフル人” Was Not a Slur

About a month before the posts quoted above, Oka herself wrote:

ポルトガル語史料に出てくる「カフル人」は基本的には「カフラリアの人」という意味で、蔑称は込められません。ただし、「カフラリア」自体に「カフィールの土地」という意味がありますから、ポルトガル人の船に乗り込んでいたインド洋を往来するムスリムの水先案内人などが使っていた言葉かと。

https://x.com/mei_gang30266/status/1832578569320722684

Translation:

In Portuguese sources, “カフル人 (Cafre = Kaffir)” basically means “a person from Cafraria,” and it does not carry a derogatory nuance. However, since “Cafraria” itself means “land of the kafirs,” it was probably a word used by Muslim pilots and others who sailed the Indian Ocean aboard Portuguese ships.

I had seen this post of hers, and Eich-y surely had as well. That would be why he used the term カフル人 in his reply without hesitation. I translated it as “Kaffir people” because that is exactly how it appears in the sources as Cafre. Student X’s assumption that eich-y “intentionally” used a racial slur was based on his own bias.

Even if eich-y had truly written something racist, the idea that quoting it meant I held the same racist views makes no logical sense.

Oka Intended “カフル人” as a More Neutral Translation

Traditionally, the Portuguese word “Cafre” has been translated into Japanese as “黒奴 (black slave).” Oka argued that this rendering was prejudiced and that it should instead be translated as カフル人.

同じです。基本的には、アフリカ東南沿岸部のカフラリアと呼ばれる海岸地帯出身者のことで、16世紀はモノモタパ王国と呼ばれる地域に凡そ相当します。Cafreはカフル人と訳すべきで、「黒奴」がすべてカフル人というわけではありません。インド人やジャワ人なども「黒奴」と呼ばれます。

https://x.com/mei_gang30266/status/1814215612832612616

Translation:

It’s the same. Basically it refers to people from the coastal region known as Cafraria along the southeastern coast of Africa, which in the 16th century roughly corresponded to the Monomotapa Kingdom. Cafre should be translated as カフル人 (Kaffir people), not “黒奴 (black slave),” and not all “black slaves” were Kaffir people. Indians and Javanese were also called “黒奴 (black people).”

原文には「Cafreカフル人」とはっきり書かれており、「奴隷」を想起させる単語は一切入っておりません。「黒奴」としたのは、昭和時代の日本人翻訳者の偏見です。私の過去のポスティングをご覧いただければ。

https://x.com/mei_gang30266/status/1815030671720747281

Translation:

The original text explicitly says “Cafreカフル人 (Kaffir),” and there is no word suggesting “slave.” Translating it as “黒奴 (black slave)” was the prejudice of Showa-era Japanese translators. Please see my earlier posts.

Perhaps “黒奴 (Black Slave)” Is Actually Better

If there are English speakers like Student X who feel hurt by the word, then even if their interpretation is academically mistaken, it may still be safer to continue translating Cafre as 黒奴, as has long been the practice.

When someone clicks the automatic translation button on X, the Japanese word “カフル人” is automatically rendered as “Kaffir” in English, like I translated it. This means that if Japanese speakers use the word “カフル人,” even without any discriminatory intent, English speakers may still misunderstand them as racists.

Translating it as “黒奴” may also not be inaccurate. Oka’s husband, Lúcio de Sousa, comments on the word “Kaffir” in a footnote:

In Asia, then, the Portuguese and their descendants used this term to refer to someone with a dark skin tone, most of the time a slave.

Lúcio de Sousa, The Portuguese Slave Trade in Early Modern Japan : merchants, Jesuits and Japanese, Chinese, and Korean slaves, Studies in Global Slavery, Vol.7, Brill, 2018. p.8

From a Japanese perspective, “カフル人” is obscure and not easy to grasp, while the two-character word 黒奴, literally “black” + “slave,” is more immediately understandable. As I will mention later, in the case of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, there has even been a movement in the United States to replace the N-word in the text with “slave.”

Yasuke and others like him who came to Japan were brought by Europeans and were not free men. The term 黒奴 is not hate speech in itself, and it may actually be a more suitable translation than “カフル人.”

I can understand the concern that the character 奴 (“slave” or “fellow”) sounds disrespectful. But if “カフル人” is unacceptable and “黒奴” is also unacceptable, then what word are we supposed to use in translation?

“Kaffir” Became a Harsh Slur During Apartheid

This word turned into a vicious racial slur during the infamous apartheid era in South Africa. The Wikipedia page on Kaffir states clearly:

While originally not pejorative, it became a pejorative by the mid-20th century and is now considered extremely offensive hate speech.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaffir_(racial_term) Accessed September 10, 2025

As an English speaker, Student X almost certainly viewed the word Kaffir through the lens of modern English.

Another Example: “Aborigine” Was Originally Latin

A similar shift can be seen in the word Aborigine, which was once used to refer to Australia’s indigenous peoples. In contemporary English, it is now often considered derogatory, and the phrase Aboriginal people is preferred.

The word’s origin, however, is the Latin phrase ab origine, meaning “from the beginning” or “original inhabitants.” It was originally a completely neutral term and was not limited to Australia.

Over time, it came to refer specifically to the indigenous peoples of Australia. Through the colonial era, it acquired negative associations, and today it is frequently treated as offensive.

Presentism: Judging the Past by Today’s Values

Should the Latin word “ab origine” be censored just because its English descendant “Aborigine” is now considered derogatory?

Of course not. That would be absurd. Judging the past by the standards of the present is what historians call presentism, and it is something that should be avoided in historical research.

Anglocentrism: Treating English as the Global Standard

The word Kaffir did not originate in English. It came from Arabic, where it meant “unbeliever.” It only came to be treated as hate speech relatively recently, in the context of modern English.

So should the Portuguese word “Cafre” found in early modern sources, or its Japanese translation “カフル人,” as well as the Japanese word “カフリ (Cafre, Kaffir)” in historical documents, be judged by the standards of modern English?

The answer is clearly no. Because that would be presentism.

The Unfairness of Anglocentrism

The word Kaffir became a slur because English speakers themselves began using it in a derogatory way.

In other languages it was not originally a slur, but in the 20th century English speakers redefined it as one. To apply that modern judgment retroactively to historical terms from different eras and cultures is unreasonable.

When English is imposed as the standard over other languages and cultures, that is linguistic imperialism. Those who oppose discrimination should not fall into an imperialistic mindset themselves.

Linguistic imperialism – Wikipedia

Going Forward, I Will Add Annotations, But…

As a linguist, I am fascinated by the origins of words and the changes in their meanings. In my previous article, I examined the difference in the meaning of the character “鬼” in Chinese and Japanese. I enjoy researching the etymology of many kinds of words.

Most readers, however, are not interested in the origins of slurs and will not take the time to investigate them. To avoid unnecessary misunderstandings like this one, I will, though reluctantly, add explanatory notes when such words appear.

Historical sources, however, contain many terms “Moor,” “Negro,” and others that modern English readers may take as slurs. To annotate all of them would be endless. I want my articles to be easy to read, not filled with footnotes.

Take the word negro: in Spanish it simply means “black.” If every single instance had to be followed by a disclaimer such as “This is not being used in a derogatory way, kust means ‘black’,” it would be absurd.

Some Historians Confront the Problem of Excessive Political Correctness

Lúcio de Sousa devotes twenty-six lines of footnotes just to the word Moor.

Whenever I am quoting from a document, I will keep the word “Moor/Moors” as it is in the original language(s). In my own narrative, I will use the more appropriate and nondiscriminatory word Muslim/Muslims. The word Moor is a misnomer, since its primary meaning, from the original Greek, via Latin, is “black,” or rather, the “black” people whom the Greeks and, later, the Romans, had encountered in the Maghreb. In order to distinguish between “white” and “black” Africans living in the Maghreb, the Greeks, and later the Romans, coined the neologisms “Berbers”—from the Greek βάρβαροι barbaroi, i.e., “barbarians”—and “Moors”—from the Greek Μαυροι mauri, i.e., “black.” Unbeknownst to them, the “Berbers” are not a race, but rather, are an ethno-linguistic agglomeration of tribes belonging to the Afro-Asiatic group whose ethnicities, due to intermarriage, can embrace people with black African blood. In Latin, Mauri came to designate the (dark-colored) inhabitants of “Mauritania,” the region between Numidia and the Atlantic Ocean. From the Greek plural form, the Latin derived the singular Maurus, -a, -um. Hence, by extension, the word meant a dark-colored person and, later, an African. Many times, the color of the Mauri was understood; hence, the Romans knew that Mauri meant “black” Africans and not Berbers. With the advent of Islam in North Africa, in the Maghreb and, consequently, in Europe, particularly in الأندلس Al-Andalūs and صقلية Siqilliyyah (Sicily), the term “Moor” became synonymous with Muslim. Islam entered the Iberian Peninsula and Sicily through Africa; the Maghreb, particularly from Morocco; and Sicily from Tunisia and Libya. Given that some Muslims were “black” or “dark skinned,” Europeans confused the two terminologies “Moor” and “Muslim,” thus making them synonymous. From the Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian, the confusion between these two words and concepts, as well as their overlapping and synonymous meaning, spread throughout Europe, thus making its way into other European languages. Needless to say, the word “Moor” is racially, ethnically, and religiously very offensive, as well as being historically and linguistically incorrect.

Lúcio de Sousa, The Portuguese Slave Trade in Early Modern Japan : merchants, Jesuits and Japanese, Chinese, and Korean slaves, Studies in Global Slavery, Vol.7, Brill, 2018. p.18

Historian Guillaume Carré laments this situation in strong words:

Un dernier point, qui pourra sembler un détail, mais qui n’en demeure pas moins un symptôme préoccupant des ravages du politiquement correct et de ses préventions ridicules dans la recherche historique. En citant un passage de ses archives où figure le terme « Maures2 » pour désigner des musulmans, l’auteur se croit obligé de justifier la présence de ce m word inscrit, semble-t-il, sur la liste noire du lexique offensant, par une note de 26 lignes, pas moins, avec une pusillanimité digne d’un séminariste terrorisé par sa première traduction de Pétrone. Alors que la chasse aux mots malséants et aux évocations gênantes amène depuis longtemps les éditeurs japonais à maquiller des reproductions de cartes anciennes ou, plus récemment, à vouloir censurer un atlas sur leur propre pays3, il est inquiétant, pour ne pas dire plus, qu’un chercheur éprouve presque le besoin de s’excuser de citer ses sources dans son ouvrage, comme si désormais il devenait impossible, voire dangereux, de faire confiance à l’intelligence du lecteur et à sa capacité de faire la distinction entre le vocabulaire des archives et les opinions d’un historien.

2: L’auteur ne donne que la traduction anglaise « Moors ».

3: Voir l’édition japonaise de l’ouvrage de Rémi Scoccimaro, Atlas du Japon. L’ère de la croissance fragile, Paris, Autrement, 2018.Translation (Using ChatGPT):

https://journals.openedition.org/slaveries/3641

One last point, which may seem like a detail but is nonetheless a troubling symptom of the damage wrought by political correctness and its ridiculous precautions in historical research. By quoting a passage from his archives where the term “Maures” appears to designate Muslims, the author felt compelled to justify the presence of this m-word—apparently blacklisted as offensive vocabulary—with a note of no fewer than 26 lines, displaying a timidity worthy of a seminarian terrified by his first translation of Petronius. While the hunt for unsuitable words and awkward references has long led Japanese publishers to disguise reproductions of old maps, or more recently to attempt censorship of an atlas of their own country, it is worrying, to say the least, that a scholar now feels almost obliged to apologize for citing his sources, as if it had become impossible, even dangerous, to trust in the intelligence of the reader and in their ability to distinguish between the vocabulary of the archives and the opinions of a historian.

Summary:

- In historical research, it is absurd to add long disclaimers every time a supposedly offensive word appears, apologizing “this is not my opinion.”

- Such political correctness undermines academic freedom and shows a lack of trust in the reader’s intelligence.

- Readers should be able to distinguish between the language of primary sources and a historian’s own views.

- A climate where scholars feel compelled to apologize simply for quoting words from historical documents is dangerous and troubling.

I Don’t Want English to Be Treated as the Global Standard

In my articles, I work with Portuguese and Japanese historical sources. Modern English has nothing to do with them. What Carré pointed out is absolutely right. I do not want readers to approach these texts through the lens of contemporary English sensibilities.

Of course, I try to be considerate toward English-speaking readers since I publish in English. But to be frank, when I am writing about the history of early modern Portugal and Japan, I want readers to interpret it in light of Portuguese and Japanese values of that time. Is that really such an excessive expectation?

I am not a native English speaker, nor have I ever lived in an English-speaking country. I am unsure that the word Kaffir needs to be so strictly restricted, even to the extent of introducing presentism into historical studies. Being required to conform unconditionally to English speakers’ sensitivities feels Anglocentric, even like linguistic imperialism. That seems an excessive demand to place on the writer.

The N-word in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Mark Twain’s late 19th-century novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn contains the N-word 219 times. In the United States, there have been repeated attempts to censor or even ban the book.

If the N-word in this novel were censored for the sake of political correctness, readers would lose the raw portrayal of slavery that Twain wanted to convey.

Was Mark Twain himself a racist? Certainly not. The story is very clearly opposed to slavery.

My own post about the N-word had a similar purpose. I was warning that what Oka quoted in Chinese was essentially the N-word. Does that make me a racist?

If such words are censored so that Japanese readers cannot see them, they will fail to understand why the Chinese word is offensive and why it must not be used. Readers need the ability to understand why a word remains visible in the sources and why the word is problematic.

A Restaurant Named Kaffir Lime

In Tokyo, there is a Thai restaurant called カフィアライム (Kaffir Lime.) Naturally, the owner did not choose this name with any racist intent. Kaffir lime is simply the name of a fruit native to Southeast Asia that is widely used in the region’s cuisine.

Remember also that the word Kaffir originally comes from Arabic, where it meant “unbeliever.” The fruit probably received this name because, from a Muslim perspective, it was associated with non-Muslims such as Buddhists or Hindus.

To accuse the restaurant owner by saying, “Why are you using ‘Kaffir,’ a racial slur against Black people? You must be a potential racist!” would be anachronistic nonsense.

According to this Wikipedia article, The Oxford Companion to Food has encouraged the use of an alternative name, mankrut lime (derived from the Thai word makrùut). Perhaps one day even this restaurant will be criticized by English speakers as being “racially offensive.”

The Japanese “外人” and the Chinese “外人”

Here is another example. In Japanese, the word for “foreign person” is “外国人 (gaikokujin),” which literally means “outside country person.”

- 外: outside

- 国: country

- 人: person

As an informal variant, people often drop “country” and simply say “外人 (gaijin)”. Some foreigners in Japan prefer this short form and even use it to describe themselves.

For me, however, growing up in rural Japan as a Southeast Asian half, this word almost always carried a derogatory nuance when it was used to me. Those who treated me with respect always used the formal term “外国人” instead.

I still tense up whenever I hear it because I was repeatedly called “外人” in a demeaning way as a child. I deeply understand the feelings of people who are sensitive to slurs.

On the other hand, in Chinese, “外人” simply means “outsider” or “someone from outside,” and nothing more.

Even though I dislike the Japanese word “外人,” I would never demand that the Chinese word “外人” be censored.

Kanji characters originally came from China and were later adopted into Japanese. To regulate Chinese usage based on Japanese sensibilities would be absurd. Likewise, it is inappropriate for Oka to insist that Chinese words must carry the same meaning as they do in Japanese, projecting Japan’s unique sense of “鬼” (oni, ogre) onto Chinese.

I believe that each language and culture deserves respect, and that no one should judge or impose the values of one language onto another.

Linguistic and Cultural Isolation in the United States

It is often said that Americans are uninterested in foreign countries. Some dismiss this as a stereotype, but in my experience it applies to many Americans. News in the United States rarely covers international affairs in depth.

The country may be multiethnic, but in practice it is unified under English, the world’s most dominant language. Relatively few Americans feel the need to study other languages because English is understood almost everywhere.

This cultural background can foster the unconscious belief that their language is the global standard.

I studied Thai at university and spent a year studying abroad in Thailand, so I naturally know kaffir lime. I also studied Chinese and therefore know that the Chinese word “外人” is not the same as the Japanese word “外人.”

The sense to view words in relative terms does not come naturally to many Americans. English may function as a global lingua franca, but that is only for convenience. In historical research and language studies, English meanings are not the absolute standard.

I Wish Student X Had First Questioned His Own Assumptions

At the start of his message, he declared that he had to choose between learning the language he had loved since childhood and keeping his self-respect, and that he chose self-respect.

From there, without leaving me any chance to defend myself he created a narrative in which I was assumed to be a potential racist, while he was preserving his dignity by cutting ties with a “racist teacher.”

Even if I had later clarified that it was all a misunderstanding, it would have been too awkward for him to continue the lessons. For me as well, being unfairly branded a racist based on a misinterpretation was extremely unpleasant.

Kaffir Lime!? How could you give your restaurant such a name? You must be a potential racist! For the sake of my dignity, I will never eat here!

But… it’s simply the name of a fruit used in Thai cooking…

…

You would not be able to eat at that restaurant after such an exchange. Even if you did, the meal probably would not taste good.

I Wish He Had Asked “Why?”

Before concluding that I was a potential racist, I wish he had checked the timeline of the quoted posts more carefully. Even if he had missed Oka’s post, he could have at least paused his anger and asked me, “Why did you quote a post that contains a slur?”

Why did you use the word “Kaffir”? That’s a racial slur.

No, it’s the name of a fruit used in Thai cooking.

Oh, so it wasn’t meant as a slur. After looking it up, I found that the fruit is real, and the word originally came from Arabic meaning “unbeliever.”

In that case, you could have enjoyed your Thai meal without discomfort. You might even have learned something new, expanding your world with both a fruit and a word you had not known before.

I Believe Student X Was a Good Person

Although his message expressed anger, I could also see that he chose his words carefully to show me as much respect as possible. I believe he was a good person. That is why it saddens me that such a misunderstanding caused our lessons to be canceled.

I also understand why he was sensitive to slurs. I myself belong to an ethnic minority. That is exactly why I was warning against Oka, who used the Chinese N-word so casually. I truly wanted him to understand that.

It Is Hard to Question One’s Own Preconceptions

Even Mihoko Oka, a researcher with a Ph.D., would not admit that she was caught in the prejudices of the Japanese language. I realized how difficult it is for many people to recognize their own biases through the debates over Yasuke,

There is a Chinese phrase, 先入为主 (xiānrù wéi zhǔ), which literally means “what enters first becomes the master.” It perfectly describes how troublesome preconceptions can be. I try to remind myself not to fall into 先入为主.

Perhaps I do so because I have been exposed to many different languages and values, and I am used to viewing words in relative terms. Such a perspective is not necessarily common in monolingual societies like Japan or the United States.

For Those About to Learn a Foreign Language: Don’t Assume English Meanings Are Absolute

When learning a language, it is essential to question your own preconceptions. Japanese, for example, has many “wasei-eigo” (Japan-made English words). Laptop is called “ノートパソコン (nōto pasokon, which means notebook personal computer),” and company employee is “サラリーマン (sararīman, which means salaryman).”

To native English speakers, these words may look strange or incorrect. But please do not dismiss them outright. They are perfectly “correct” within Japanese since they were created in Japan and are used as everyday vocabulary.

Language is alive, and its changes are part of what make it fascinating. I hope readers can experience and enjoy that richness.

In Conclusion: Though I Lost Something, I Also Learned Something

This was a sad incident that cost me a student. But I also learned something valuable: the dilemma between faithfully translating historical terms and being considerate toward modern English speakers.

If I translate faithfully, then “カフル人” can only be rendered as “Kaffir” or “Kaffir people.” Some might argue that I should leave it in Japanese characters, but that would make the meaning opaque and defeat the purpose of translation.

In the end, I will translate it as “Kaffir people” and add annotations for English readers. Like Carré, I have many reservations about this practice. But to prevent unnecessary trouble, this is the approach I must take.